Dry Cleaning

#

Transcription of the above image

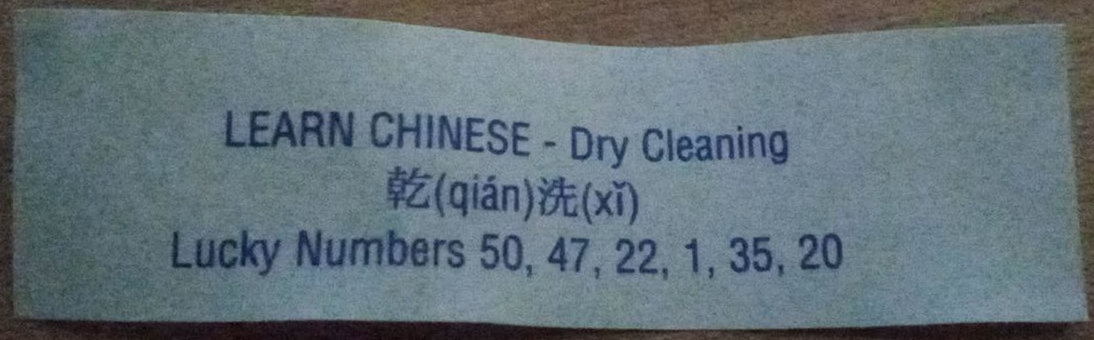

LEARN CHINESE — Dry Cleaning

乾(qián)洗(xǐ)

Lucky Numbers 50, 47, 22, 1, 35, 20

Figure 1: The piece of paper in question!

Fortune cookies are not Chinese. At best, they’re Japanese, and really, the modern form that we know is an American invention. The transfer in association from Japanese to Chinese (or rather, from Japanese‐American to Chinese‐American) seems to largely boil down to the gastronomic preferences of Americans at the time (viz. the first half of the 20th c.):

“A lot of Chinese restaurants were owned by Japanese,” Stephen said, noting that there wasn’t a lot of demand for sushi back then. “They opened Chinese restaurants as a means to an income.”

The use of English & Sinitic (rather than Japanese) text on fortune cookies would have to wait until the incarceration of Japanese‐Americans in concentration camps during WWII, as implied by an anecdote relayed by Lee:

The little slips of paper inside had originally been written in Japanese back then, she remembered. Only later, she recalled, did the messages appear in English. “When did they change?” I asked curiously. “I think they changed by the time we came out of camp.”

LEARN CHINESE

##A reader unfamiliar with Sinographs, however, may have a hard time telling the difference. Japanese calls them 漢字 ⟨kanji⟩ /kän.zi/ [kã̠ɲ̟d͡ʑi], and although the use of hiragana &/or katakana is a dead giveaway, particularly short texts (e.g. a single word or name) may have few or no kana. This paper, however, clearly implores the reader to “LEARN CHINESE”, so let’s take a look at what it wants us to read:

The use of Hànyǔ Pīnyīn implies that this is MSM. Remember that the Sinitic languages are highly diverse, so MSM is generally mutually unintelligible with other Sinitic lects — and even with some other Mandarinic lects!

Because immigration from Sinophone regions to the U.S. well pre‐dates the PRC’s largely successful push for MSM as the dominant language of its territory, Chinese‐Americans have traditionally been overwhelmingly non‐Mandarin‐speaking. Actual statistics are difficult to come by because people unfortunately tend to just use the blanket term “Chinese”, but still, there’s an historical association with the Yue languages, especially Taishanese & Cantonese.

This fortune cookie takes, I suppose, a more modern approach. There’s just one problem: it reads the first character incorrectly!

Fig. 1 gives the reading qián /kʰjan˧˥/ [t͡ɕʰjɛn˧˥] (vaguely like English *chyen with a rising tone), which Wiktionary glosses as: “first of the eight trigrams (bāguà) used in Taoist cosmology, represented by the symbol ☰; first hexagram of the I Ching, represented by the symbol ䷀”, ultimately from PST *m‐ka‐n “sky; heaven; sun”. I don’t reckon that drycleaning has much to do with Taoist cosmology, so that’s probably not right.

Indeed, 乾 is more usually read as the etymologically unrelated gān /kän˥/ “dry, dried, arid; [to] dry”, which is clearly the intended reading. This is from PST *kan “[to] dry”.

Even more character confusion

##But we probably expected to see simplified characters, considering that their readings are given in Pīnyīn, right? The simplified form of 乾 with the correct reading is 干.

For better or worse, this character was chosen for its homophony, so 干 also has readings like “concern, be implicated in; [obsolete] (a) shield” (from a PST root having something to do with shields or defense) and a few other homophonic or near‐homophonic (e.g. gàn) morphemes.

Thankfully, the second character is unambiguously xǐ /xj∅˨˩˦/[1] [ɕi˨˩˦] (vaguely like English she with a falling‐&‐then‐rising tone) “wash, rinse; clean; redress”. Phewf.

FTFY

##Endnotes

##- ↩︎

Using /∅/ to represent a null (nonexistent) syllable nucleus.

References

##| [Lee08] | Jennifer 8. Lee. . The Fortune Cookie Chronicles: Adventures in the World of Chinese Food. Grand Central Publishing; New York, NY. |

|---|