Dry Cleaning

Transcription of the above image

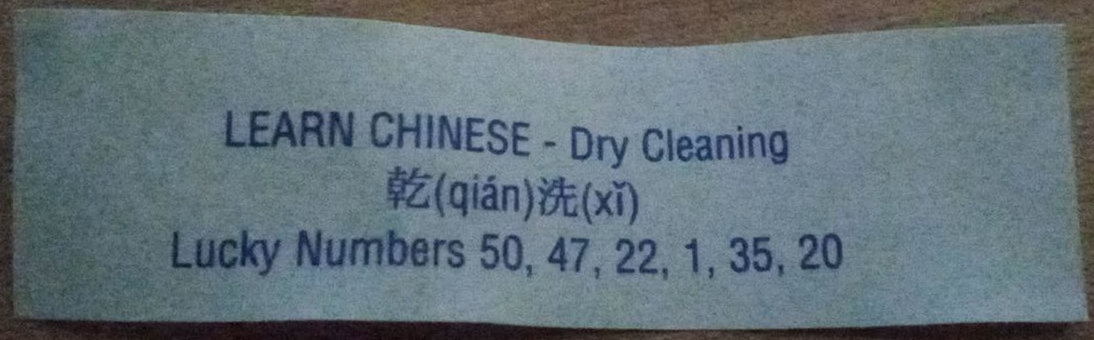

LEARN CHINESE — Dry Cleaning

乾(qián)洗(xǐ)

Lucky Numbers 50, 47, 22, 1, 35, 20

Figure 1: The piece of paper in question!

Fortune cookies are not Chinese. At best, they’re Japanese, and really, the modern form that we know is an American invention. The transfer in association from Japanese to Chinese (or rather, from Japanese‐American to Chinese‐American) seems to largely boil down to the gastronomic preferences of Americans at the time (viz. the first half of the 20th c.):

“A lot of Chinese restaurants were owned by Japanese,” Stephen said, noting that there wasn’t a lot of demand for sushi back then. “They opened Chinese restaurants as a means to an income.”

The use of English & Sinitic (rather than Japanese) text on fortune cookies would have to wait until the incarceration of Japanese‐Americans in concentration camps during WWII, as implied by an anecdote relayed by Lee: